6 Things to consider when writing your first DSL

Here we will be focusing on the L in DSL, which is “Language” for humans to interface with your domain.

I don’t know about you, but I see DSLs everywhere these days. GraphQL, SQL, Kusto, jq expressions and Bicep just to name a few. The fact is, DSLs can useful. Case in point would be Bicep vs JSON ARM Template (Azure Resource Manager). Although Bicep is not necessarily an ergonomic language, but it is miles better than crafting ARM template by hand. Plus, because it is a language, it has some perks that come with a language and not a generic serialization format like JSON. For example, syntax checker and auto-complete (you can achieve the same with JSON Schema, but I am trying to be biased here!).

Creating a language or DSL can be intimidating and rightly so. Especially in this day and age where programmers have certain expectations for a new DSL. Here are some of the things you might want to consider before creating one of your own.

1. Choose the grammar wisely

This would be syntax. The thing that users would be spending most of their time with your DSL.

A good starting point would be, do you create a new syntax or follow an existing one? If you choose to be inspired by an existing language, do you want to follow a mainstream syntax like Java or go indie and adopt Lisp?

This depends on the domain and your goals. Generally, adopting an existing familiar syntax is highly recommended because it reduces the friction of learning your DSL and familiar things are more approachable. Bonus point, some languages have their grammar file available, either in their source control or at some parser generator repository. That can help accelerate your DSL development time.

Compared to the other parts of a DSL, grammar and syntax are quasi permanent. Once you decide on it, it stays. If you change it, it becomes another language entirely. cough-Perl 6-cough.

2. Is the parser hand-made?

A good segue into parsers!

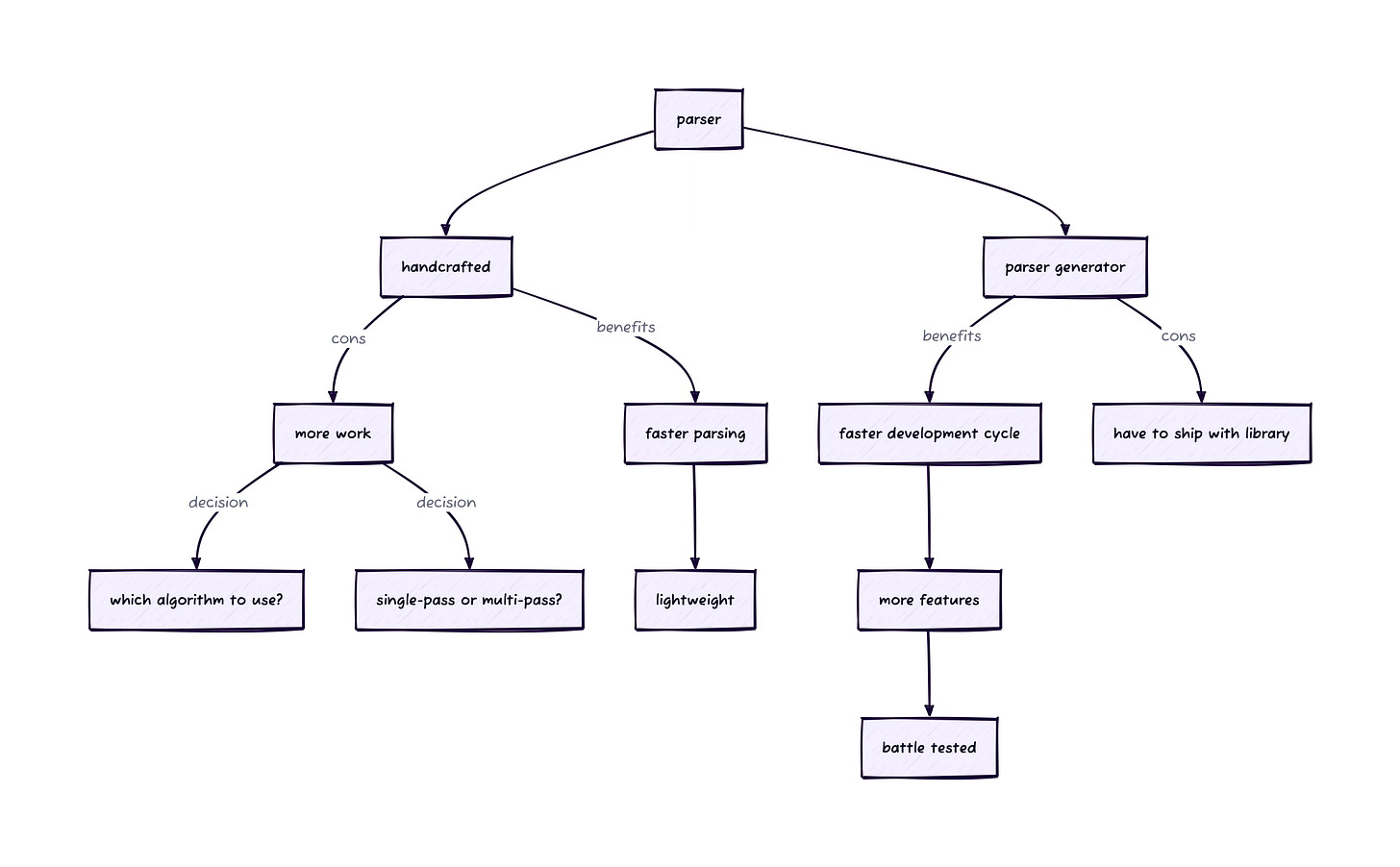

The question is, would you like to hand-craft your own parser or would you like to use a parser generator?

There are pros and cons to both choices. Writing your own parser would potentially mean a faster parsing time and you have full control of how you would like your parser to behave. If execution speed matters a lot, this is potentially a good route to take. On the less fun side, writing parsers can be a lot of work and few things to decide on.

For example:

Would it be a single-pass or multi-pass parser? i.e. do you want to do everything in one go or split the job into stages, e.g. tokenizing, parsing etc?

What algorithm is it going to be? LL, LR, LALR, Packrat or etc? Depending on your syntax and grammar, certain algorithm is more suitable than others.

If you are going with the parser generators, e.g. Antlr or Yacc, you’ll be using a battle tested library. Plus, the development cycle could be a lot faster because all you need to do is write the grammar and fill in the missing parts in the generated code. And some parser generators come with convenient features.

Antlr, for example, generates a resilient parser, which does not fail at the first syntax error it encounters. That would come handy if you want to create a language server protocol (LSP). And the AST comes with metadata which will be useful for reporting errors back to users. The downside, however, you’ll need to ship parts of the parser generator library together. Depending on your requirements, this might be either a none issue or a cause for rejection.

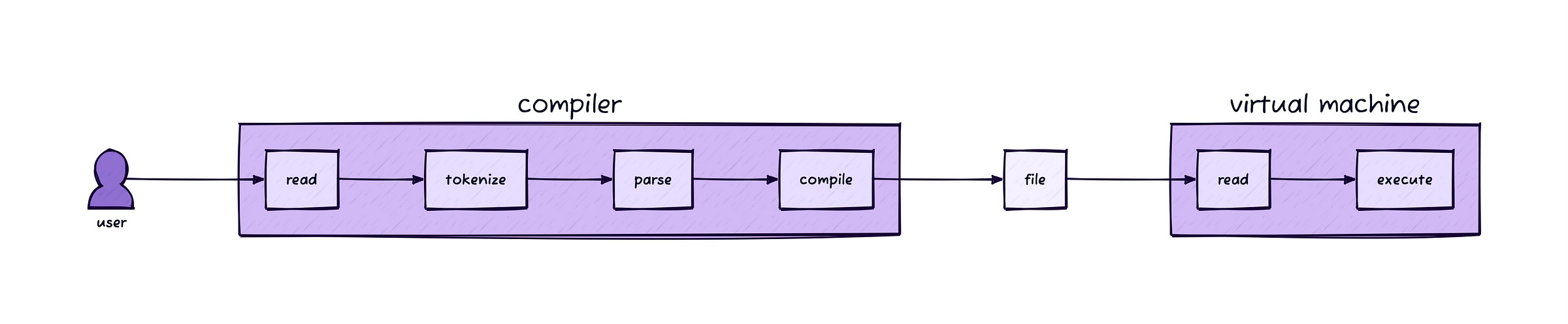

3. Do you want interpreted or compiled?

Almost all DSLs have to go through the same operations. Depending on the creativity and intent of the creator, you may split or join these multiple phases. For an interpreter, the steps might look something like below and they are done immediately one after the other.

Tokenize: reading the DSL into a stream of accepted characters.

Parse: organizing the characters into groups of data structures, Abstract Syntax Tree (AST). Syntax errors are usually discovered here, depending on choice of AST.

Execute

If you are feeling adventurous, you might want to split the “Execute” stage from the other two, then it might look something like below, which is a variation of a compiled language.

Compile Phase

Tokenize

Parse

Compile

Optional: static analysis

Execute phase

Execute

A non-exhaustive list of the pro and cons of going either interpreter or compiled

Interpreter

Pros:

Simpler and faster to implement.

Cons:

Typically, slower to execute than compiled version. Some slowness can be attributed to the AST. Traversing a tree is slower than a sequence (compiled).

Compiled

Pros:

Usually, faster to execute

Smaller output file size. This probably matters only if you need to transmit the file or store it somewhere where there is limited space.

Cons:

More complex to implement

Requires either to implement a VM or compiled to machine code (or C)

4. Do you need a type system?

I’ll keep it simple, if your DSL does not allow creating new types, i.e. it has fixed types, then, it most probably just needs a basic type system and type checker. The majority of DSLs should be in this category.

On the other hand, if you like challenges and your DSL has capabilities to create types, then you have decisions to make :) After syntax, types are most likely the hardest to change. Especially when considering that certain types systems demand a certain style of syntax. For example, Hindley-Milner is much easier to apply to functional languages.

You'll also want to decide if the domain is better served with a statically or dynamically typed language. And it would be tremendously helpful if you already have a type system implementation example that you could refer to. Type theories are nice and dandy, but translating that to real-world implementation is another story.

Personally, I would start the DSL light with fixed types.

5. Would the users prefer a declarative or imperative language?

Declarative DSL would focus more on what to do instead of how to do it. For example, in GraphQL, users just need to describe what data they want but cannot really control how to get the data. On the other hand, imperative DSL would focus more on how to do things.

But, these are not really black and white options, it is a spectrum. Your DSL can be declarative, but have facilities for control-flow and creating procedures. More often than not, DSLs are declarative.

To decide which style to adopt, I would start from the use case of the DSL and move backwards.

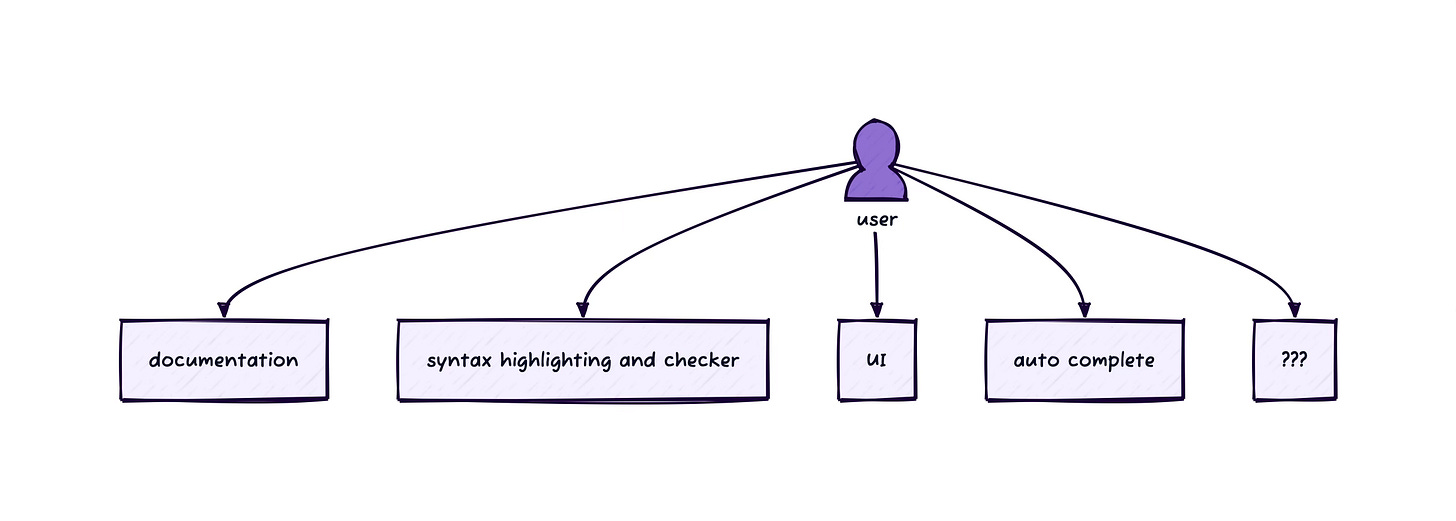

6. Developer experience requires good tooling

The main goal is to reduce the friction of using your DSL to bare minimum.

For starters, it would be nice to have syntax highlighting and checker. Thanks to modern development, we don’t have to develop custom editors for your DSL. Investing some effort in building a language server would allow your language to be used nicely in modern editors such as VSCode and NeoVim.

Other tools can be developed depending on the capabilities of your DSL. For example, if your DSL executes in the cloud, then a pleasant web interface to run it would be delightful, like how Azure provides for Kusto Queries. If the DSL is an attempt to replace any existing format, e.g. JSON, then a migration tool would a great idea to promote adoption. Not forgetting documentations for onboarding new users and allowing them to be productive as quickly as possible.

The better the experience of using your DSL, the more people would want to give it a try.